- Toolkits

- Are You Ready to Talk?

- Beyond the Line

- Blocking Gender Bias

- Edgy Veggies

- First-Gen Ascend

- Fishbowl Discussions

- Measuring Mobility

- Peaceful Politics

- Plot the Me You Want to Be

- RaceWorks

- Rethinking Stress

- Space Reface

- Team Up Against Prejudice

- United States of Immigrants

- Kit Companion: Map Your Identities

- Kit Companion: LARA

- Collections

- Action Areas

- About

Inclusion of Other in the Self (IOS) Scale

Measuring Mobility Toolkit > Measure Selector > Inclusion of Other in the Self (IOS) Scale

Inclusion of Other in the Self (IOS) Scale

Factor: Being Valued in Community

Age: Child, Teen, Adult

Duration: Less than 3 minutes

Reading Level: Less than 6th grade

What

Social psychologist Arthur Aron and colleagues (1992) developed the single-item Inclusion of Other in the Self (IOS) scale to measure how close the respondent feels with another person or group.

Who

The IOS has been given to respondents as young as five years old (Cameron, 2006), as well as to teens and adults. It has also been used with respondents living on a low income and previously incarcerated respondents (Folk et al., 2016; Mashek, Cannaday, & Tangney, 2007).

How

INSTRUCTIONS

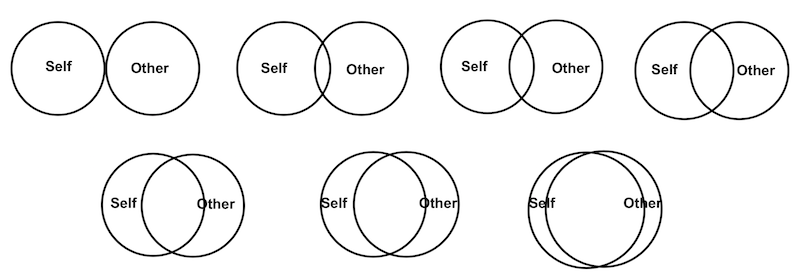

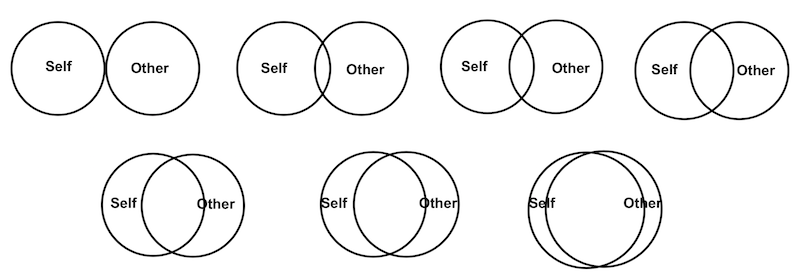

Respondents see seven pairs of circles that range from just touching to almost completely overlapping. One circle in each pair is labeled “self,” and the second circle is labeled “other.” Respondents choose one of the seven pairs to answer the question, “Which picture best describes your relationship with [this person/group]?” Researchers indicate what person or group the “other” circle stands for (e.g., “your romantic partner,” “your parents,” “your community,” etc.)

To score this scale, researchers record the number of the pair (1 to 7) the respondent selected.

RESPONSE FORMAT

Respondents choose a pair of circles from seven with different degrees of overlap. 1 = no overlap; 2 = little overlap; 3 = some overlap; 4 = equal overlap; 5 = strong overlap; 6 = very strong overlap; 7 = most overlap.

Which picture best describes your relationship with [person/group]?

Why It Matters

Feeling connected with other people drives outcomes that relate to social mobility. For instance, in studies where the “other” on the IOS scale is a romantic partner, high scores are associated with marriage quality and can even predict whether a dating couple will still be together in three months (Aron et al., 1991). Other studies show that getting and staying married, in turn, improves both health (Horn, et al., 2013) and wealth (Lichter, Graefe, & Brown, 2003) — both of which contribute to upward mobility (Card, 2001; Halleröd & Gustafsson, 2011)

Relationships with groups may also be important for social mobility. In studies where the “other” on the IOS is the community, the closer previously incarcerated respondents felt to their communities, the greater their residential stability, homeownership, and educational and vocational status (Mashek, Cannaday, & Tangney, 2007; Folk et al., 2016).

HEADS UP

Although it is plausible that increasing one’s connection with a particular person or group can spur upward mobility, no study has yet directly tested this idea.

References

Aron, A., Aron, E. N., Tudor, M., & Nelson, G. (1991). Close relationships as including other in the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(2), 241-253.

Aron, A., Aron, E. N., & Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(4), 596-612.

Cameron, L., Rutland, A., Brown, R., & Douch, R. (2006). Changing children’s intergroup attitudes toward refugees: Testing different models of extended contact. Child Development, 77(5), 1208-1219.

Card, D. (2001). Estimating the return to schooling: Progress on some persistent econometric problems. Econometrica, 69(5), 1127-1160.

Folk, J. B., Mashek, D., Tangney, J., Stuewig, J., & Moore, K. E. (2016). Connectedness to the criminal community and the community at large predicts 1‐year post‐release outcomes among felony offenders. European Journal of Social Psychology, 46(3), 341-355.

Halleröd, B., & Gustafsson, J. E. (2011). A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between changes in socio-economic status and changes in health. Social Science & Medicine, 72(1), 116-123.

Horn, E. E., Xu, Y., Beam, C. R., Turkheimer, E., & Emery, R. E. (2013). Accounting for the physical and mental health benefits of entry into marriage: A genetically informed study of selection and causation. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(1), 30-41.

Lichter, D. T., Graefe, D. R., & Brown, J. B. (2003). Is marriage a panacea? Union formation among economically disadvantaged unwed mothers. Social Problems, 50(1), 60-86.

Mashek, D., Cannaday, L. W., & Tangney, J. P. (2007). Inclusion of community in self scale: A single‐item pictorial measure of community connectedness. Journal of Community Psychology, 35(2), 257-275.